The growing ubiquity of SkillTRAN and its flagship Job Browser Pro ("JBP") makes it imperative to use and understand the strengths and weaknesses of JBP standing alone and incorporated into OASYS. Searching for light unskilled work using OASY S provides the list of DOT codes sorted by job numbers.

We start with the observation that JBP list sets out 1,572 DOT codes ranging from 458,000 jobs to 1 job with 124 DOT codes representing no jobs. JBP lists 52 DOT codes as representing 10,000 or more jobs. The 1,572 DOT codes represent about 3.5 million jobs. The top five occupations represent over 1.2 million jobs, more than a third of the total. The top five answers on the board are:

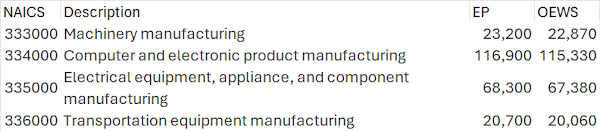

We know where most of these jobs exist. Cashiers work predominantly in retail trade. Power-screwdriver operator is a manufacturing occupation. Housekeeping cleaner work in accommodation in almost have the jobs. Marker works in retail trade, hence the DOT industry designation. And counter attendants work in hotels and restaurants. What we intuitively know is backed up the Occupational and Wage Employment Statistics ("OEWS") and the Employment Projections ("EP").

In estimating job numbers for a Social Security disability case, the first question is whether the work represents full-time work. The second question asks for the other physical demands of that full-time work.

1. Cashiers

The O*NET reports that 43% of cashiers represent full-time work. JBP estimates 32% of jobs represent full-time work.

The 2023 Occupational Requirements Survey ("ORS") states that cashiers have a maximum lift/carry of 25 pounds at the median. Labor currently defines light work as up to 25 pounds occasionally. SSA has not re-defined light work but to make the program fit with Labor's data, expect that change before the abandonment of the DOT. The 2018 ORS estimated that 35.5% of cashiers engaged in light work. The 2023 ORS does not give a strength estimate by neat classification.

The estimate of strength requires consideration of maximum weight lifted, frequent weight lifted, occasional weight lifted, and constant weight lifted.

The constant (68% or more of the day) lifting a negligible weight (one pound or less) is light work even if that is the only lifting requirement. Constant lifting of up to 10 pounds is medium work. Constant lifting of up to 25 pounds is heavy work.

Frequent lifting of a negligible weight is sedentary work. Frequent lifting up to 10 pounds is light work. Frequent lifting up to 25 pounds is medium work. Frequent lifting up to 50 pounds is heavy work.

Occasional lifting includes the category of seldom in the ORS and probably the separate measure of maximum lifted.

What percentage of cashiers engage in light exertion? I use the 2018 first wave final estimate, 35.5%. It is a final first wave estimate. The data does not permit a clean demarcation of 25 versus 20 pounds lifted.

If a witness wants to use JBP, use the 32% full-time estimate. If a witness does not use JBP, use the 43% full-time estimate.

Based on the data, there are probably between 1.1 and 1.5 million cashiers working full-time. There are probably between 391,000 and 525,000 light cashier jobs.

The SSA doctors (CE and DDS) reflexively endorse about six hours of standing/walking in a workday. How many cashiers do not have an expected work requirement of standing/walking six hours? None. The 2018 data set reports standing (including walking) 87.5% of the workday; the 2023 data set reports standing 80% of the workday. The choice of sitting or standing does not limit the amount of standing. The choice applies where the employer endorses sitting but the person can stand or where the job has some functions that sit and some that require standing and the employee can choose when to perform those two different functions. It is not a measure of a sit-stand option. A choice exists in 4.4% of jobs on the 2023 ORS and 5.4% of jobs on the 2018 ORS.

The number of light unskilled cashier jobs that stand/walk six hours or less in a full-time workday is not statistically represented but is clearly less than 10% of jobs. Stated differently, there is no basis for taking administrative notice of full-time cashier work with standing/walking six hours or less.

2. Power-Screwdriver Operator

SkillTRAN puts power-screwdriver operator in SOC OEWS group 51-2090, assemblers and fabricators. OEWS use of code 51-2090 includes 51-2092 and 51-2099. It is a composite. The Occupational Outlook Handbook (OOH) also reports 51-2090. I expect that Labor will break out miscellaneous assemblers and fabricators in the next OOH/OEWS releases.

The OEWS and EP/OOH report between 1,489.280 and 1,498,300 wage and salary employment jobs for assemblers and fabricators.

The ORS reports that 41.8% of assemblers and fabricators engage in light work -- lifting/carrying up to 25 pounds.

The ORS reports that less than 63% of assemblers and fabricators engage in unskilled work.

Using the BLS methodology:

1.5 million x 41.8% = 627,000 light jobs

627,000 x 63% = 395,010 light unskilled jobs

At the mean, assemblers and fabricators stand/walk 84.2% of the day. At the 25th percentile, assemblers and fabricators stand/walk 85% of the day. The ORS reports < 5% of jobs require sedentary exertion. This not statistical basis for the inference that there are assembler and fabricator jobs that do not require more than 75% of the day standing/walking and do not represent sedentary work. (8 x 75% = 6).

3. Housekeeping Cleaner

SkillTRAN puts housekeeping cleaner in SOC/OEWS code 37-2012, maids and housekeeping cleaners. SkillTRAN estimates that 54% of maids and housekeeping cleaners represent full-time work. The O*NET reports 86% of maids and housekeeping cleaners represent full-time work.

The OEWS and EP/OOH report between 826,230 and 1,215,400 wage and salary employment jobs.

The ORS reports that 70.5% of maids and housekeeping cleaners engage in light work -- lifting/carrying up to 25 pounds.

The ORS reports that less than 91.4% of maids and housekeeping cleaners engage in unskilled work.

Using the BLS methodology:

1.2 million x 70.5% = 846,000 light jobs

846,000 x 91.4% = 773,244 light unskilled jobs

At the mean, maids and housekeeping cleaners stand/walk 95.7% of the day. At the 10th percentile, maids and housekeeping cleaners stand/walk 87.5% of the day. There is no statistical basis for the inference that there are maids and housekeeping cleaners jobs that do not require more than 75% of the day standing/walking.

4. Marker

SkillTRAN puts marker in SOC/OEWS code 53-7065, stockers and order fillers. SkillTRAN estimates that 58% of stockers and order fillers represent full-time work. The O*NET reports 68% of stockers and order fillers represent full-time work.

The OEWS and EP/OOH report between 2,872,680 and 2,861,200 wage and salary employment jobs for stockers and order fillers.

The ORS reports that stockers and order fillers have a maximum lift/carry of 25 pounds at the 10th percentile -- BLS defined light work.

The ORS reports that less than 85.5% of stockers and order fillers engage in unskilled work.

Using the BLS methodology:

2.8 million x 10% = 280,000 light jobs

280,000 x 85.5% = 239,400 light unskilled jobs

At the mean, stockers and order fillers stand/walk 91.8% of the day. At the 10th percentile, stockers and order fillers stand/walk 80.0% of the day. There is no statistical basis for the inference that there are stockers and order fillers jobs that do not require more than 75% of the day standing/walking.

5. Counter Attendant

SkillTRAN puts marker in SOC/OEWS code 53-7065, stockers and order fillers. SkillTRAN estimates that 58% of stockers and order fillers represent full-time work. The O*NET reports 68% of stockers and order fillers represent full-time work.

The OEWS and EP/OOH report between 2,872,680 and 2,861,200 wage and salary employment jobs for stockers and order fillers.

The ORS reports that stockers and order fillers have a maximum lift/carry of 25 pounds at the 10th percentile -- BLS defined light work.

The ORS reports that less than 85.5% of stockers and order fillers engage in unskilled work.

Using the BLS methodology:

2.8 million x 10% = 280,000 light jobs

280,000 x 85.5% = 239,400 light unskilled jobs

At the mean, stockers and order fillers stand/walk 91.8% of the day. At the 10th percentile, stockers and order fillers stand/walk 80.0% of the day. There is no statistical basis for the inference that there are stockers and order fillers jobs that do not require more than 75% of the day standing/walking.

We have examined a third of the light unskilled jobs according to SkillTRAN and its various products. We know from commonsense confirmed by the ORS that light work often requires more than six hours of standing/walking during a full-time workday. This raises the problem of agency policy, SSR 83-10.

6. Resources

Every person that represents people at hearings needs access to and learn how to use SkillTRAN products Job Browser Pro and/or OASYS. Every representative must understand and know how to use the O*NET, ORS, County Business Patterns, the Occupational Outlook Handbook, the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, and the Employment Projections. SkillTRAN links to or reproduces many of these government publications. So too does OccuCollect.

7. Agency Policy Is Misunderstood and Applied

SSR 83-10 uses the mantra that light and medium work require approximately six hours of walking or standing in a workday. The agency no longer specifies the amount of standing and walking. The state agency does, "about 6 hours." Most vocational experts assume that the absence of a statement implies that the person can stand/walk the whole day. More importantly, SSR 83-10 refines the approximately six hours of standing/walking with the statement, "Sitting may occur intermittently during the remaining time." The remaining time is two hours. Intermittently does not mean the entire time. SSR 83-10 is misunderstood by the agency because it won't read the next sentence for light or medium work. Intermittently means something different than the entirety of the rest of the time.

___________________________

Suggested Citation:

Lawrence Rohlfing, The Top Five Job Numbers for Light Unskilled Work, California Social Security Attorney (October 1, 2024) https://californiasocialsecurityattorney.blogspot.com

The author has been AV-rated since 2000 and listed in Super Lawyers since 2008.